Brother, can you spare a worm tooth?

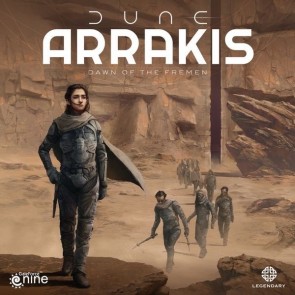

In 1982 EON (the groundbreaking design team of Olotka, Kitteredge, and Eberle) released Borderlands, a “game of the barbaric future” that found players locked in an intensely interactive, Diplomacy-inspired struggle across a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It was a brilliant game– yet the game never seemed to reach the popularity or uptake of their previous designs, Cosmic Encounter and Dune. There was a pretty decent computer game implementation of it in the 80s called Lords of Conquest and Fantasy Flight for whatever reason decided to slap an unappealing steampunk motif on it for a 2013 redevelopment called Gearworld, but the real legacy of this game has been in its ahead-of-its-time streamlining, the resource production, and development methods that echo in games like Catan and Scythe. Now, here in 2020, EON is giving the design another go with Jack Reda and Greg Olotka on the design team and Gale Force 9 presenting Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen.

And, as someone who once made a print and play copy of the original game, I can tell you that not only is this game still compelling, vital, and singular, it also feels like it has effectively arrived as a worthy successor to Dune. Set during the early history of Arrakis, when Fremen tribes were first settling the sands, this game exhibits once again these designers’ understanding and mastery of Dune’s concepts and themes. I was thrilled when the game was announced as a “new” Dune game from this team, but I was actually even more excited to discover that it was a revision of Borderlands.

The old adage “they don’t make ‘em like this anymore” applies here. This is not a game of solitary tableau building and passive-aggressive drafting. There are no catch-up mechanisms and you don’t get victory points just because you followed the rules. There are no tracks or meters, there aren’t even any of EON’s signature special powers. It is rather a game where everything is on the map- every resource, unit, and element of the game is visible and available for analysis. It is also a game where you absolutely must negotiate, barter, wheedle, intimidate, and cajole. So due warning for those adverse to direct competition and treachery.

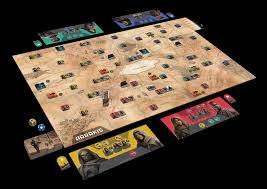

Beginning with the Harj (the initial setup phase), the board is seeded with four resources (water, food, worm teeth, and of course spice) at specific sites, randomly assigned. Players also fill the board’s territories with their Tribesmen and women (with multiple skintones represented) and place rock barriers between territories to protect strategically vital assets. Development tokens such as Worms, Stillsuits, and Crysknives can be purchased to increase mobility and combat strength and there are Scavenge cards that may be picked up that could introduce things like Maula Pistols and Ornithopters in the game. It takes 90 minutes on the short end, but can definitely go much longer as it shares with Dune a sort of volatility in terms of how it plays out, especially if players are really digging into the negotiation element. The primary win condition is for a player to control three Sietchs (which are built with one of each resource or four spice), but alliance victories between players are possible as is a “Council Vote” win when players determine that one amongst them has an unbeatable position.

Conflict is deterministic. An attacking player places a marker in the region they wish to try to seize from another tribe. Both the attacker and defender may call for aid from adjacent territories with promises of trades, future support, or whatever as potential leverage. Once the numbers shake down, the victor is determined. Because the Fremen have a highly structured, formal society based on their mutual heritage, if you defeat someone in combat you owe them a Water Debt, which they may use later to block attacks should you wish to continue hostilities or to exchange into resources.

Now, where this game gets really interesting is in how the resources and development tokens work. Everything is on the board at all times, players do not have personal holdings. This means that in order to build a Crysknife in the Western Sands, you have to have either two spice or a water and a worm tooth in the Western Sands. And of course, there is not necessarily a way to generate those resources in the Western Sands so you have to transport those resources there by moving them with your units (and taking advantage of formal alliances to move through allied territories) or trading with others to accomplish the goal. And then, that Crysknife is on the board and can be moved around to strategically support attacks or defenses. This all adds a level of depth to gathering resources and working out the logistics – but with some players, it can also grind things to a halt.

It’s almost a no-luck game, but there are a couple of key elements where die rolls and card draws come into play. One is the Scavenge deck, which are cards that sometimes provide a little surprise in combat, give a resource boost, or put a development token such as a Jubba Cloak or Ornithopter on the board. I like the cards a lot even if they very much feel like a sort of “bolted on” addition. They add a lot of Dune flavor, which I can never get enough of, and they provide just a little unpredictability and drama. I also really like that they are mostly tradeable- they can be a key element in brokering a deal.

Another random factor is in the Production phase, where a D12 roll controls whether or not production sites bear fruit (or spice, as the case may be). Players have a Thumper token with a full moon and crescent moon side, and you kind of place a bet on what you think the die roll will be and the result determines what produces and if your Thumper was successful in calling a Worm, which is a development token that you place on the board and your Fremen can ride it while transporting goods. Likewise, the Trade and Shipment Phase is also metered by the die and this creates shortages and surplus while also possibly barring a player from trading their way into a Sietch for the turn. There are also die results that call for players to vote on whether the phase happens or for the lead player to decide, both of which can make for some interesting discussions.

This whole logistics angle is, for me, the crux of what makes the design so compelling. Players are forced into cooperation while they are also locked in very direct competition for territory, resources, shipping rights, and development tokens and there is very little to hide your intentions behind. This whole Catan-like resource production and development scheme is supported by an equally intriguing system driving above-the-board, para-mechanical interactions between players. Like in Cosmic, alliances of convenience are always in play virtually every turn and like in Dune, formal alliances (which must be – get this- approved unanimously during the Council phase) change the win conditions but provide significant benefits.

With that said, this is to my mind a four player game, period. Most of the games I’ve played so far have been three players and they’ve been fun and engaging, but the absence of a fourth seat can be felt. Likewise, a two player game is totally possible (described by Olotka as more of a “chess match”) but I feel like it’s just not where the game is at its best because its greatness rests in the interactions and how players leverage those interactions to engage with the mechanisms. Truth be told, I probably wouldn’t ever turn down a two or three player game because I’m just happy to get this great game to the table whenever I can.

Arrakis: Dawn of the Fremen is a 40-year-old design freshened up for a modern audience with the Dune livery respectfully and vividly applied – it totally feels like a Dune game, and it almost seems like it was always meant to be a game about the Fremen establishing themselves on Arrakis. It is also a very different game than their previous Dune, and it is a much more formalistic and structured game than Cosmic. Yet I do think that it remains the least accessible of this trio, especially for more recent generations of game players who, quite frankly, might not be accustomed to or inclined to play games that are treacherous, stabby, and extremely interactive like it is. But for those that are, this is one of the best reprints in some time, a forgotten classic that has always deserved a higher profile.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?