“Imagine that the cow is a sphere.”

This is the punch line to an old Physics Professor's joke. I could repeat the setup, but it isn't funny enough to warrant the effort. The punch line on its own is sufficient to reveal the absurdity of how physicists view the world. They do it for good reason. Physicists need to paint the world with big fat brushes so that the large concepts they consider don’t get lost in the minutia. Having the cow shaped as a rectangle would likely work, but having it shaped as a cow makes for some serious topological challenges when you’re writing a proof. Though absurd, round cows are useful when you’re paid to figure out answers to very big questions.

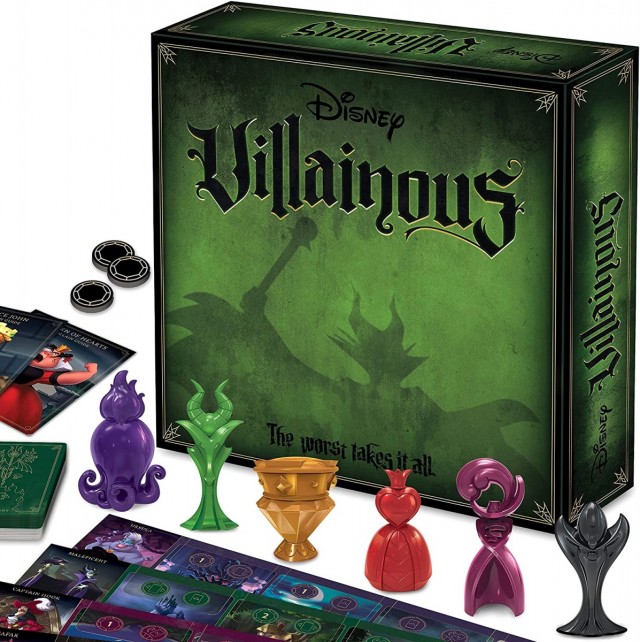

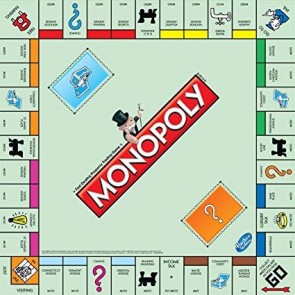

It is with this frame of mind that I look at objects in my life. I’m a mathematician myself, but I worked with a bunch of egghead physicists in the electromagnetic field for ten years (and programmed their logic into machines) and that changed the way I think. It is with this unorthodox perspective that I view the game of Monopoly. Most see it as a take-chances financial game where good money management and a bit of luck gets you rich. Not me. I see it as a mostly-closed system where heat repeatedly rolls from one side of a manifold boundary to another. I appreciate this isn’t the most straightforward way to view it, but in Monopoly’s case there’s a pretty straightforward abstraction largely due to its simple, insular nature. Simply put, Monopoly is a leaky universe, well-bounded, with specific points of entry and exit for all energy.

Alright, I’ll try to paint this into a more concrete picture.

I know, the next sentence should read “imagine that Monopoly is a sphere.” I won’t go quite that simple. Instead, let's imagine Monopoly is a muffin tin. Imagine six cups in a circle (i.e., a six player game) like the one below. The cups are nice and deep so they can hold plenty of energy:

It might be a custard tin, but the concept is the same. That hole

in the middle is a nice feature for this metaphor. We'll get to that in a minute.

I like to bend the outside edges up a little in my mind so that little hole in the middle is kind of at the bottom of a bowl-shaped tin.

Like all things in the universe Monopoly's concept has matter and energy, but Monopoly’s matter isn’t very exciting. Its energy is. Board games are verby things and that means energy. That’s where the thermodynamics comes in. “Thermodynamics” loosely means “the motion of heat” (heat=energy to physicists) and it is what makes our little Monopoly universe tick. It’s where the action is, and it’s where you can get a real understanding of the nature of the game. That may sound a bit murky, but I’ll try to model it with our real-life muffin tin.

This muffin tin is our physical model for the energy flow in Monopoly, and most importantly it defines the boundary lines for our game. Simplifying complex problems in physics (e.g., turning cows into spheres) is important, but so is defining the edges of the problem. Drawing correct boundaries around the right parts allows important pieces to be front and center while extraneous details are culled. There are pieces to be left out of Monopoly, so let’s start figuring out what’s in and what’s out.

What's Inside.

The Players. Congratulations, you’re in. Pick a heart, any heart. That heart cup in our tin is you, the player. More to the point, that cup is you and your current status in the game (i.e., winning, losing, or somewhere in between). Each cup in our bowl-shaped tin represents a player and all his holdings in the game, dollars, properties and otherwise. I’ll describe how you can visualize your status in your personal cup in a moment.

The Bank. The bank is essentially out. There’s good reason for this, because unlike banks in the real world that have well-defined limitations on available funds (and are another player at the real-world-economics gaming table) the bank in Monopoly is designed to be a never-ending supply of dollars. It's passive. It’s an important part of executing the rules, but it’s misleading from an analytical perspective. It’s an uninteresting part of the equation. So the bank is out. Now, I said essentially out earlier. To some extent the bank can be looked at as “the universe beyond the boundary”. It's a little system next to ours that we’re going to need to avoid violating an important law in physics. I’ll cover that in a bit, but for the moment indulge me. Let us consider the bank beyond the edge of our muffin tin.

The Dice. Out. The dice themselves in spite of their sinister reputation are essentially innocent bystanders in this game. The results of their input into the game are going to be modeled by the other pieces.

Alright, here’s where it starts to get interesting.

The Properties (board locations and buildings). Properties are in, and they’re one of the two most important parts of this entire discussion. Remember, we’re talking thermodynamics here so we’re going to be talking about energy. More to the point we’re going to be talking about the flow of energy, one of the most fundamental goals of the thermodynamics field of study. Properties themselves aren’t energy, but they’ll play an important part in how the energy moves, and that’s a big deal in Monopoly. Energy flow is the core of the game, because the energy in Monopoly is . . .

The Money. The money is in. It’s the heart and soul of the game. It’s the victory condition, the life blood. The amount of money you currently hold, your energy level, is a fundamental gauge of your health in Monopoly. Undoubtedly the properties you own are an important part of that assessment as well, but without cash you lose. Money is the energy, the heat in the game. The flow of that heat a) into the game, b) between individual player cups on our Monopoly muffin tin, and eventually c) out of the game is where the heart of Monopoly’s play can be discerned from a physicist’s perspective. That flow is fundamental. It’s the entire game abstracted into its three basic actions. The balance of those actions is what makes Monopoly work.

Let’s start with a simple example to illustrate how this energy we’re talking about flows. Somebody lands on one of your properties, and they owe you $150. They owe you some lifeblood, some energy. Where does that money come from?

Let's phrase that question better: where DID that money come from? Each of those dollars is on a journey. Obviously the player that landed on your space pays you out of their hand, but where did that money come from before that? Where did it originate and where will it eventually end? What is the life story of each of those dollars? This is an important question, particularly in light of the knocks Monopoly gets regarding many of its house rules. Money arrives in the game, money moves around, then money leaves. I’m not talking about the piece of paper with $1 written on it that's used over and over again, I’m talking about the abstract “dollar” value concept, entering play as a drop of energy landing in someone’s muffin cup, sloshing from one cup to the next over and over again, and then eventually draining out of our tin into the great beyond never to return. Those three categories, entry, movement, exit, apply to real-life economic theory every bit as much as to our game here, so this is big-deal stuff. This is how economists view dollars, how governments manage money supply.

Entry. Energy (i.e., money) arrives in our muffin tin in one of three ways:

- Starting dollars are given to each player. At $1500 each, our six-player game starts with $9000. That’s a fair chunk of energy considering Baltic avenue charges a mere $2 for an overnight stay.

- Dollars drop into your cup via Community Chest or Chance cards. Bank Error in Your Favor gets you $200. The rest are under $100, generally under $50. Compared to the $9000 to start this isn’t a huge addition of energy into the system. No one turns it down but it’s a minor source at best. It’s there and can be looked at as a slow, reasonably steady input of energy throughout the lifespan of the game. A slow warming of the cups in our tin.

- You receive dollars for passing Go. Early in the gamvice $200 feels like a windfall of epic proportions, largely because Baltic’s $2 charge is so insignificant in comparison. The pass-Go money isn’t to be sneezed at – with six players it’s pumping $1200 into the system every time the group circles the board, adding half again to the starting money after just four trips. With a couple of Chance and Chest cards thrown into the mix there’s about $14,000 worth of input energy after four round trips. That covers plenty of overnighters even on the swanky side of the board.

This is what physicists do when they look at systems. They look to see how energy flows into it, around it, and out of it. One of the foundational concepts of physics is that all of that energy can be accounted for. It moves, but it doesn’t go away. By setting our boundaries where we have, we can look at the game’s state at any moment in time and assess each player with a fundamental question: how energetic are they? How hot? How much money? You do this all the time when you play boardgames, assessing a player’s shot at the win from all their positional information. You quantify them in your head without doing the math. In Monopoly it’s easier than most. We can imagine our muffin tin as containing different amounts of heat in each cup, a representation of the number of dollars (and fungible assets) each player has available to them. Each cup starts the game at a certain temperature (the Starting Dollars), heats up as dollars magically drop into it from the great beyond (Chance and Community Chest Dollars), and has a more or less dependable injection of heat over time (passing Go). I tend to imagine it as each cup actually being hot to the touch and glowing some shade of red orange or blue, but I tend to be more tactile when I envision this kind of thing. For the more visually-oriented, it’s just as easy to imagine a certain amount of hot liquid in each cup, more liquid meaning more heat for a particular player. That’s likely a better visualization in this case because of the cups -- liquid flows between cups when players land on properties, and it flows down our little hole in the center of the pan into oblivion when payments go to the bank.

The three items above make up the total of the inflow – there’s only three ways energy enters our Monopoly system from beyond the boundary, so our system needs to get along with the heat it gets from these sources. If everything remains static (say if all six players land in jail simultaneously and stay there turn after turn) all will be well. Each cup will have a specified amount of energy and nothing will change. A pretty boring game, but a valid condition nonetheless.

We all know that’s now how things play out in a real game of Monopoly. Before discussing the flow from one cup to another, let’s enumerate the ways that money can exit our muffin tin.

Exit. Money exits the game, never to return. Three ways:

- Purchasing Properties. Running anywhere from $60 to $400, money spent to acquire properties irrevocably disappears from our system. Earlier I said that the bank was out of the picture, but that we needed to consider it the “universe beyond the boundary”. Here is the role it plays – it magically sprinkles money into the game (discussed above), and it gobbles up money that dumps out of the individual cups. This latter action is what happens when properties are purchased. Money leaves the system permanently. A good investment though, right? Properties create money? Nope. Properties move money. They’re these magical attractors that tug energy out of your opponent’s cups into your own, but they don’t bring any additional money into the game. The amount of energy within the boundaries of our system has been significantly decreased with your purchase, applying pressure on all players since the muffin tin has just lost the very thing each needs to survive. It’s a little slice of Musical Chairs acting as a subordinate mechanic in the larger game system. This energy has fallen off of our tin, gobbled up by the bank never to be seen again.

- Purchasing Buildings. As with properties, money is drained when buildings are purchased. Our magical attractors get a big jolt of additional “tuginess”, but again, that attraction is only moving energy, not creating it. The overall temperature of the system has gotten smaller again. Cooler. That is, there’s less and less money to work with for all players. As a player your hope is that the buildings you just sunk energy into will do more damage to your opponents than they’ll do to you. That’s the edgy part of Monopoly. That’s the conflict in the play. You have to deal damage to yourself short-term in the hopes that it will do more damage to others long-term.

- Chance and Community Chest, Income Tax, Jail, etc. There are additional outflows that act more or less as a dependable drain from the system. A few are quite large. Over the period of an entire game it’s likely everyone pays their share, and to some extent this keeps the game in check in conditions where people aren’t able to squander money on buildings. That is, it drains off what Go and other cards are pumping in. It’s like somebody is bumping the pan, spilling your cup a little bit. Energy drains down the center hole into oblivion.

So I’ve described the inflow and outflow of energy in our system, what remains is what happens in the middle. You can likely figure that out for yourself at this point – our energy sloshes from one cup to another, each player moving money to other players' cups based upon what their roll of the dice dictates. This money is staying on our muffin tin, moving here and there, cycling within the boundary lines. With the "all other" energy inflows/outflows largely in equilibrium (Income Tax, Luxury Tax, Cards, Go, etc.), what remains to affect the outcome of the game is how much money the players choose to flush in hopes of attracting more of what remains (i.e., “purchases”). The energy in the system wanes over time, and often one attractor becomes significantly stronger than the others. This is the strategy in Monopoly – build better “money-attractors” on the board in the form of monopolies and buildings. Nothing is guaranteed – the motion of energy on our muffin tin as it is bumped and banged by dice rolls can send our hot liquid from one cup to another in odd ways. If your cup sloshes empty, you’re out of the game. The energy doesn’t need to disappear; it simply needs to disappear from your particular cup. As each player falls out of the game the number of cups gets smaller. More opportunities for purchase present themselves, more materials are purchased, more energy is dumped off the tin, and attractors get stronger. The "end" of Monopoly starts on turn one and moves slowly, but it finishes far faster than most give it credit for.

When played by the rules Monopoly's universe is a pretty solid example of equilibrium and control. You have an initial starting temperature based upon the starting money in the game. Money slowly flows in via Go and a few cards. Money slowly flows out via cards and a few spaces. The money that remains is subject to each player’s choice of purchases. It’s an unusual session where money doesn’t get dumped overboard quickly, and the system cools down as each player spends. Well at least that was the designer’s intention. House rules that put money at Free Parking (I’ve seen as much as $500 and once played with a group where all money paid in taxes and for cards was thrown into the middle as well) artificially raise the temperature of the game. Our original three sources of money get a fourth partner, and a big one at that. The result is, in spite of spending and sloshing, cups remain full for significantly longer because the bank keeps dumping free energy into it our system. As the overall system temperature rises it’s harder for 100% of any cup’s heat to slosh away and playtime stretches. The longer play stretches, the more free energy dumped in without a corresponding outflow, and the system's temperature spirals uncontrollably upward. Engineers don’t like systems whose temperatures spiral uncontrollably upward. It's not a healthy condition.

It’s not Monopoly’s nature either. In spite of most people’s perceptions, Monopoly is about doing without. Monopoly is about doing more with less, about scavenging a dwindling resource. It’s usually not perceived that way – most see it as a game about getting rich. But there’s no victory threshold, no magic dollar amount to attain. You win Monopoly by losing less than everyone else, by holding onto at least one remaining dollar as everyone is feverishly tossing them overboard. Monopoly is mutually assured destruction where each player intentionally takes actions to damage the game-state. To some extent I think that’s why the game is so unpopular today. Monopoly is the very antithesis of cooperative play. Monopoly is about dropping a lit grenade at the feet of the guy next to you, calculating that he’s a little bit closer to where it will go off than you are. What’s worse, as each player pulls a pin, others need to follow suit just to stay even. As in James Earnest's Falling, you win at Monopoly by hitting the pavement last. It's not a happy ending. The good news is that, although an ugly lesson, it's one you can learn from a board game instead of real life.

S.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?