Other games have built on Twilight Struggle's mechanics.

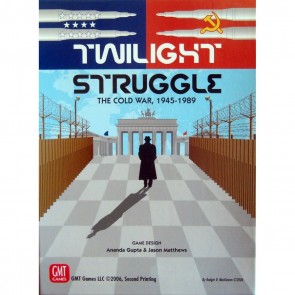

Twilight Struggle (2005, Ananda Gupta and Jason Matthews, GMT Games) is a former #1 ranked game on Boardgamegeek.com, and at this writing is still the #1 ranked wargame on the site. GMT’s all-time bestselling game combines area control with a popular wargame mechanic, the card-driven game (CDG) engine introduced by Mark Herman in We the People (1993, Avalon Hill). Twilight Struggle puts several twists on the CDG mechanic, though. As CDGs had developed until Twilight Struggle, most featured cards that could be played for operations (points used to place stuff or move it around) or to trigger events, but not both. Twilight Struggle introduces a challenging decision point—if you play a card for operations, and it contains an event beneficial to your opponent, they get to play the event. Twilight Struggle also features a Space Race track—a way to dispose of your opponent’s events. You can earn rewards in the Space Race, or suffer from falling far behind. Scoring in Twilight Struggle is based on victory points but is initiated by play of scoring cards. Either player can draw scoring cards, which can be a blessing or a curse. You know when scoring is coming, but you have fewer cards to make use of the knowledge. This evolution in the CDG mechanic was crucial to Twilight Struggle’s success and is now the foundation mechanic for a growing family of games.

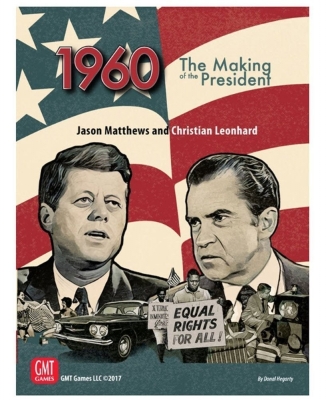

1960: The Making of the President (2007, Christian Leonhard and Jason Matthews, Z-Man Games, current version from GMT Games) was the first follow-up published. The theme changed to a pivotal United States presidential election. 1960 retained the area control mechanic— keeping with the election motif, players “carry” states rather than control them. The operations/event card mechanic is also there, but with a twist. A player must pay to activate an event card played by an opponent for operations. The payment is a “momentum counter” earned by card play. Momentum counters are often in short supply, which adds a bluffing element to the game. If I play this card, will my opponent use a precious counter? Can I fool my opponent into using the last counter on a lesser event, leaving them with none when I play a much stronger event card? 1960 also has rules for candidates making personal appearances around the country and resolving the election’s famous televised debates. Players win by winning the election via electoral vote count, not by gathering victory points. 1960 is clearly a descendent of Twilight Struggle but not a clone—the system is adapted thoroughly to reflect the electioneering theme.

Next came 1989: Dawn of Freedom (2012, Ted Torgerson and Jason Matthews, GMT). 1989 follows the Twilight Struggle model closely, shifting the focus to the Cold War’s end and Eastern Europe’s resulting anti-Communist movements. The Space Race becomes a Tiananmen Square track, and scoring is still based on regions (countries) and card play. The players are not nations, however. They are political forces—communists vs democrats. 1989 adds two major features to the Twilight Struggle game engine. Spaces in 1989 represent more than geography—each space also has a socio-economic icon identifying it as a student space, an elite space, a farmer or worker space, etc. Some event cards affect spaces with certain icon types rather than geographic regions—for example, a card event might allow a player to place markers in intellectual spaces or church spaces. The other addition is a second card deck for Power Struggles. Power Struggles occur whenever a country is scored and determine whether the country remains communist-controlled or goes democratic. Card play during a Power Struggle resembles combat in We the People or Hannibal. Players get a number of cards based on the number of spaces controlled, and they attempt to play cards their opponent cannot match. The first player who fails to match loses the Power Struggle and possibly some strength in the region or some victory points.

13 Days: The Cuban Missile Crisis (2016, Asger Harding Granerud, Daniel Skjold Pedersen, Jolly Roger Games and Ultra PRO) is Twilight Struggle’s baby brother. It uses the same operations vs. event mechanic, but there are only twelve areas on the board to control, and a leisurely paced game can be completed in half an hour or so. 13 Days has a couple of additions to the model. One is hidden agendas—players can score bonus points based on goals kept secret from their opponent. Another is three DEFCON tracks—military, political, and world opinion. Placing multiple cubes to control areas raises your DEFCON level on one track. If one or more of your DEFCON levels is too high at turn’s end, you’ve triggered nuclear war and lost the game.

The most recent addition to the family is Europe in Turmoil: Prelude to the Great War (2018, Kris Van Beurden, Compass Games). Europe in Turmoil plays more like 1989 than Twilight Struggle. It is also more conceptually abstract than either. Set during the run-up to World War I, Europe in Turmoil has to convert a multi-polar environment into a two-player game. Instead of communists and democrats, Europe in Turmoil has authoritarians and liberals. Authoritarians are something like the Central Powers, while liberals are kind of the Allies—but countries may not end up in the alliance they joined historically. Like 1989, Europe in Turmoil has socio-economic icons on its spaces and countries to score instead of regions. There are, additionally, independent spaces belonging to no country or region. The Space Race becomes the Naval Race between Britain and Germany. Instead of Power Struggles, Europe in Turmoil has two stability decks. During scoring, each player chooses one stability card from their deck and plays it to alter the situation before tallying up the victory points—so scoring is not a sure thing. Europe in Turmoil also has not one, but two methods for determining which side wins The Great War. The default involves dice rolls with modifiers, but there is also a method using a set of mini-decks called mobilization cards.

One other game deserves brief mention here: Labyrinth: The War on Terror, 2001-? (2010, Volko Ruhnke, GMT Games). Labyrinth uses the mechanic of an operations card activating an opponent’s event, but it does not otherwise adhere closely to the Twilight Struggle model. But that’s a discussion for another day.

Your humble author has only included games he owns and plays in this list. If there are other games that belong here, please let me know.

Games

Games How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?